Tomorrow is my dad’s birthday. He would be astonishingly old now—124—since he was born in 1903 and was fifty when I was born. It’s funny how time works. I have him frozen just as he was when he died in 1972, when I was nineteen years old. He was just a few weeks away from his sixty-ninth birthday, but he would not make it.

He died of small-cell lung cancer, an especially aggressive form of cancer most often caused by cigarette smoking. This was indeed the case with my dad. He smoked unfiltered Camels for as long as I can remember, often lighting a new cigarette from the end of the one he had just finished. The smell of tobacco seemed woven into his clothes, his truck, even the air of our house. At the time, it felt ordinary—almost part of being grown.

My father loved driving by the alfalfa fields and commenting on what a good crop it was. Or heading out to our farm to feed the cows, then stopping by the pecan grove to pick up a few pecans. He had an eye for the land—noticed when the rain had come at just the right time, or when the hay was cut clean and square. He hunted and fished, hobbies that were more about relaxing than about being a real “hunter.” I don’t remember him boasting about a kill; I remember him sitting quietly by the water.

Mom said he was an exceptional dancer, which I imagine made him fun at a party. They played bridge regularly and were active volunteers at Holy Trinity Episcopal Church in my hometown of Bonham, Texas. Church was as much a social anchor as a spiritual one, and my father seemed comfortable in both worlds—the sacred and the everyday.

He smoked cigarettes, chewed tobacco, and sometimes dipped snuff. He did the latter two much to the chagrin of my mother, who thought both habits were vile. Ironically, it was the cigarette smoking—the habit she tolerated most—that ultimately killed him. Of course, she smoked too. It was a different era. Doctors smoked. Teachers smoked. Ashtrays sat in waiting rooms and on kitchen tables. No one seemed to grasp the full cost.

I wish my dad could have met my husband and my children. They would have liked each other. He would have admired Ray’s steadiness. He would have teased my daughters and slipped them pecans from his pocket. I can almost see him sitting at our kitchen table, listening more than talking, taking it all in.

I genuinely liked my dad, and I loved him. He was an easy man to like—steady, observant, comfortable in his own skin. Even now, more than fifty years after his death, I do not picture him aging beyond sixty-eight. He remains suspended there, cigarette in hand, looking out across a field of alfalfa, certain the crop will be good this year.

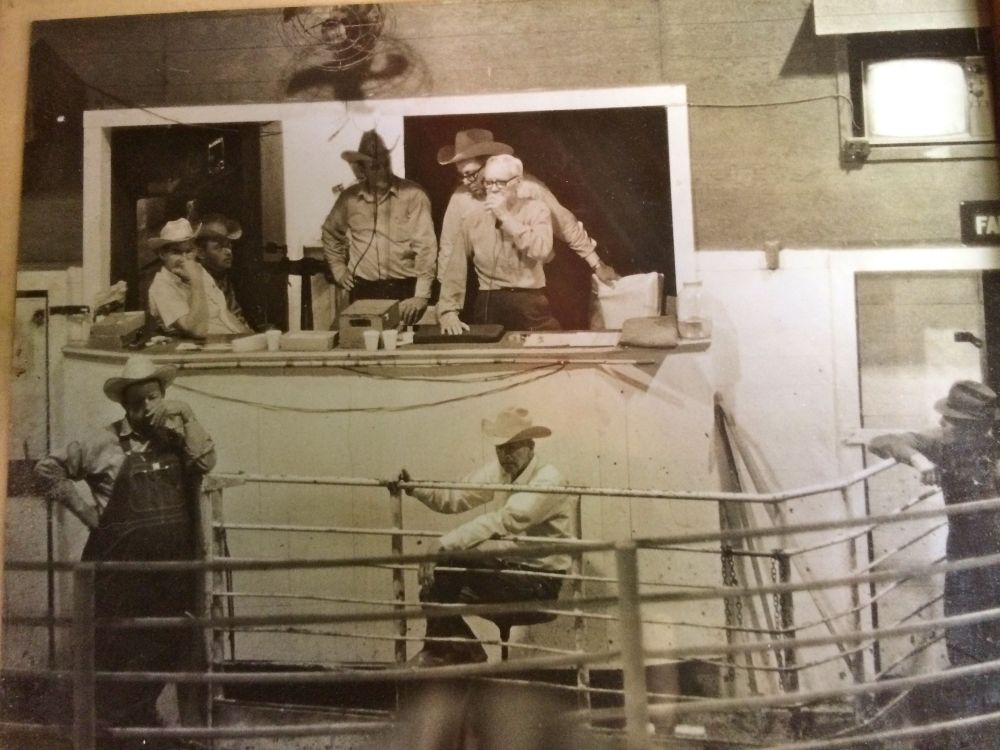

My dad is the white-haired man in the photo. This was taken a few months before he died.